In 1970, the Italian Parliament offered its people a right that may have once seemed unthinkable for the seat of the Catholic church, the very right that caused Henry VIII to depart from the church in 1534 and create the Church of England: the right to divorce.

On December 1st, the bill, first introduced in 1965, was approved 319-286, per New York Times reporting at the time, calling it “one of the most bitterly contested changes of the postwar period.” It was the “12th attempt in 92 years to institute divorce in Italy,” supported by a range of leftist parties, from the Proletarian Socialists and Communists, and opposed, unsurprisingly, by the Christian Democrats and Neo-Fascist parties.

But the path to divorce would not be easy even after the passage. It took roughly a month for the first official divorce to happen in Italy, between 28-year-old Alfredo Cappi and 25-year-old Giorgia Luisa Benassi in Modena. The Catholic contingent was already rallying its ranks to contest the legislation—they declared that they would aim to get a national referendum asking voters to overturn it. The church claimed the right to divorce went against the 1929 Lateran Treaty, which gave papal sovereignty to Vatican City and established the jurisdiction of the church courts regarding the nullification of a marriage.

It was into this landscape that Benassi emerged a divorced woman, having already been separated from her husband for six years, one of the legal grounds for divorce at the time. But even recalling the facts almost 50 years later, published on Milleunadonna, the then-73-year-old remembered the publicity and the externally-imposed shame.

“It wasn’t easy at all because, at that time, they really put me in the public eye. You know how it is, everyone was talking about me, and it wasn’t at all like it is now, that within a few months you can get a divorce and it’s not a scandal,” Benassi said. “But I freed myself from my ex-husband, and it was a relief.”

She not only had to submit to criticisms from the public at large, but perhaps more painfully, from her family. Her father was against the divorce, her mother wouldn’t talk about it, and her relatives were all divided, per Milleunadonna. And yet, when she looks back, it is not with regret but with pride for her past self.

“I freed myself from a nightmare. And to me, it didn’t seem like it happened immediately at all, there was so much chaos. It was quite a bit of work,” she said. “And if my ex-husband were to have taken up with someone else? I wouldn’t care, I would feel sorry for that poor woman.”

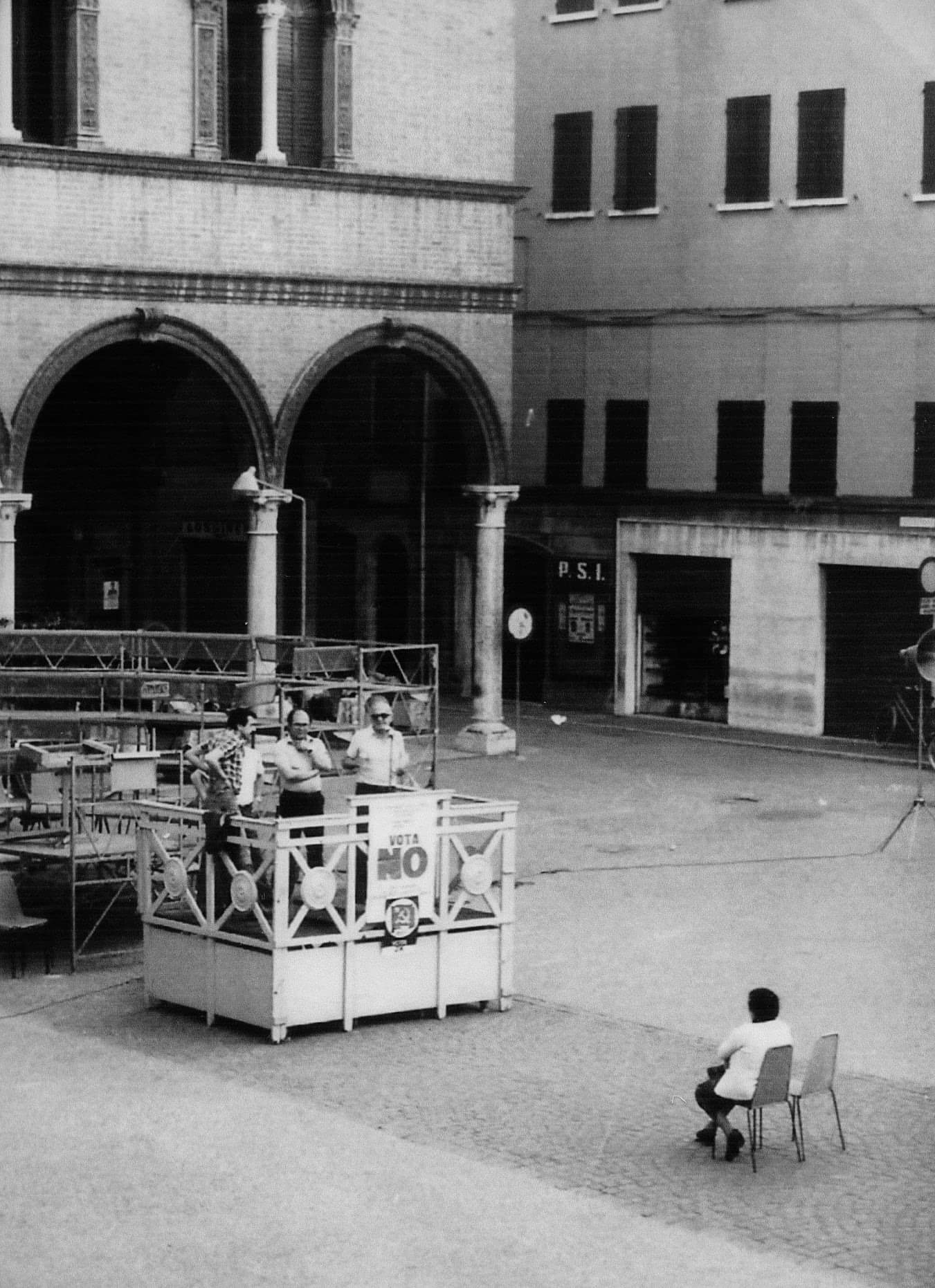

But Benassi’s victory would be hard-won and soon to be challenged. In 1974, the Christian Democrats did as promised and put the divorce legislation to a referendum. It would be the first in the Republic’s history—the last one had been the famous referendum of 1946 that officially ended the monarchy and created the Republic. And Italians certainly came out to vote—roughly 87.7% of the electorate participated, according to reporting from Il Sole 24 Ore, and 59.3% voted against the referendum, which would have repealed the law. The divide fell cleanly along regional lines—Northern and central voters voted yes to the divorce law while the South was “largely anti-divorce,” writes Patrizia Maciocchi. The number of voters was not wholly unusual—the New York Times reported at the time that parliamentary elections from two years ago had a turnout of 88.5%.

And while the Christian Democrats may have felt that divorce should not have come at all, Italy was relatively late compared to other predominantly Catholic nations of continental Europe. The Spanish Republic briefly allowed divorce between 1932 and 1939 only to see that right denied under dictator Francisco Franco and not reinstated until 1981. France, on the contrary, allowed for divorce starting in 1884, save for a brief period between 1792 and 1816 in which divorce was also legal. Portugal first introduced divorce in 1910.

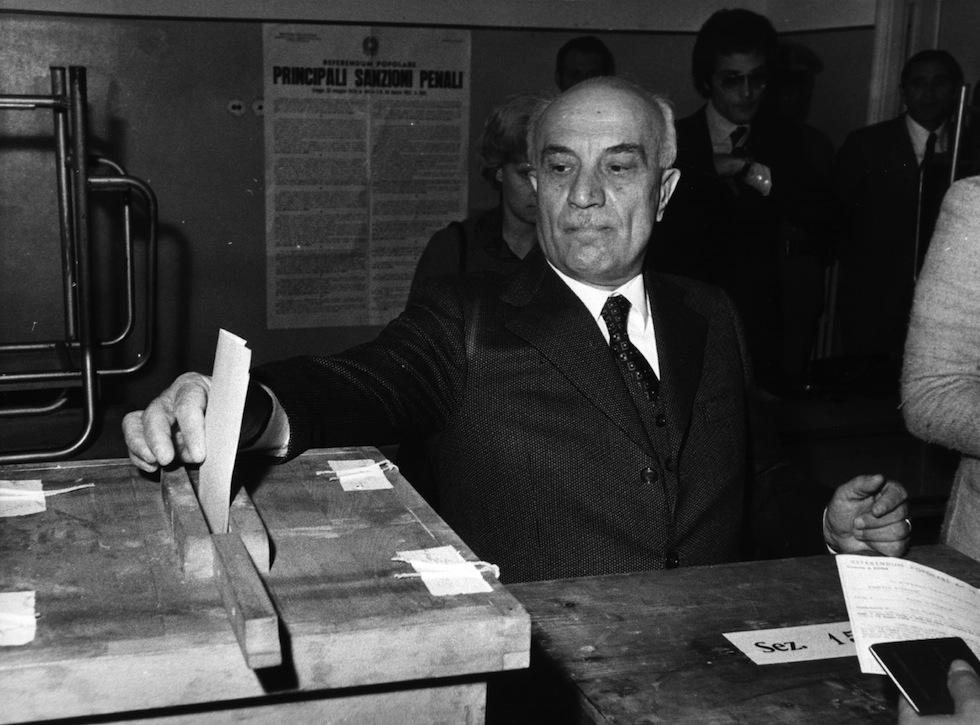

Rome, May 12, 1974 - Amintore Fanfani, Secretary of the Christian Democracy party, votes in the divorce referendum.

But the legislation of 1970 and the referendum of 1974 weren’t actually Italy’s first try at divorce. That came almost 100 years earlier, in 1878, as a unified Italy was just beginning to establish its ethos as a young nation-state. A member of Parliament introduced a legislative proposal to allow for some sort of dissolution of marriage, which reached the stage of a first reading only to falter—a path that would become somewhat of a pattern in those years for the country’s most progressive legal propositions. Between 1878 and 1902, said Mark Seymour, a professor of Italian history at New Zealand’s University of Otago, various proposals proffering the right to divorce were put before Parliament, attracting media coverage and attention, only to be eventually snuffed out.

“Unification itself was seen as a victory for progressive liberalism, but it also fanned the flames of reaction and the Church went into overdrive to try and resist radical reforms such as a divorce law,” said Seymour, who published “Debating Divorce in Italy” in 2006.

Once fascism reigned supreme in Italy from 1922 to 1943, the government under leader Benito Mussolini “was ultra-Catholic in its approach” to marriage, Seymour noted. Divorce “stayed off the table” virtually for the first half of the 20th century.

The post-war era brought the first opportunity for reopening the divorce discussion. This time, women marched in the streets for the right to divorce, “the first universal issue” that really brought them out, Seymour said. Yet Italy’s legal situation remained much the same for women pre- and post-war, he notes in a 2010 article—female adultery was punished more severely than that of a male, promoting birth control was illegal, and divorce was still seen as somewhat unthinkable. And while the Unione donne in Italia, what Seymour calls “the principal association of women on the left,” were proponents of a divorce law as early as the mid-1950s, the Italian Communist Party only began to fully support the legislation in 1969, only a year before its passage.

Part of what perhaps turned the corner was a 1956 book by Socialist representative Luigi Sansone, “I fuorilegge del matrimonio,” outlining all the ways in which the inability to divorce often left spouses, and particularly women, in an unthinkable limbo–like Italian women who had married foreign husbands during the war only to have those same husbands divorce them in their home countries while the wives retained married status under Italian law. In fact, Sansone calculated that more than four million people were affected in some way by this lack of legal marital status. This concept is reiterated in the 1970 New York Times coverage of the divorce law’s passage, likely showing that Sansone’s “fuorilegge” had some clear impact on its success. The Times even noted that spouses married to foreigners who had already received divorces in their home country would likely have access to “almost automatic” divorce in Italy.

“Sansone argued not that this was going to change the nature of marriage—that was the Catholic horror, that marriage would not be a holy sacrament,” Seymour said. “But if there were divorce, that would help all these people in terrible legal situations. It was a political strategy to get it through without too much Catholic objection.”

Whatever impact Sansone’s research might have had, by 1974, supporters of divorce were up against their next hurdle: the referendum. By that time, there were 1.7 million more women voters in Italy than men, according to Seymour’s research. Despite a strong female activist contingent, divorce advocates actually worried that women might vote against upholding the divorce law.

“When that did not happen, the anti-divorce lobby learned to their shock that Italian women’s views about marriage and the family had changed dramatically over the previous decades,” Seymour wrote in the 2010 article, “and that women could no longer be counted on to block secular initiatives.”

Fabulously dressed women protesting in support of a divorce law (1962)

In the 50 years since the advent of divorce in Italy, according to Seymour, scholars have tended to focus more on the right to abortion as a feminist victory. That was granted not long after, in 1978, although access is still limited due to roughly 70% of doctors refusing to perform the procedure as conscientious objectors.

And rather than fully lean into divorce, Italians themselves have chosen to lean out of the institution preceding it: marriage. In fact, Italy’s marriage rate was the lowest in the European Union, based on 2019 Eurostat data, ranking at 3.1 marriages per every 1,000 inhabitants. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it also had one of the lower divorce rates in the EU.

For some, it is the separation that precedes the divorce that feels almost as painful. A 33-year-old separated Roman, who has a three-year-old son, noted that “you are in standby and you live it absolutely like a divorce—that’s how it’s seen.”

“It’s very rare to find someone with a child this small that is already separated,” she said. “They will come later, surely, but it isolates you a little bit. You do things as a group and, instead, once this thing happens, it’s no longer possible.”

Separation doesn’t just mean losing some of your social bonds, she said. It also means completely reinventing yourself on an economic level—before, she might have been able to devote her full time to mothering. Now, she also has to worry about how to sustain herself financially.

Still, the untraditional, or at least unmarried, family is becoming more traditional in Italy. The average age of first marriage for men was 33.7 and women 31.5 in 2018, per data from the National Institute of Statistics. And de facto relationships, where the couple live together and effectively have some of the same civil rights as a marriage, went up from 329,000 in 1997-98 to almost 1.37 million 10 years later. In 2017, almost one out of every three children in Italy had unmarried parents.

A 34-year-old employee for a fashion company who lives in Florence falls into this category—she and her partner have been together since they were 17 and met as teens in a club. They now share a 15-month-old son, whom they had after living together for five years. And while she thinks marriage is something she and her partner will eventually do, “the conclusion of the course,” the biological pressure to have a child came before the societal pressure to marry.

“I see marriage at the legal level as a bit of a guarantee, a protection, for the mother,” she said. “I see it as a tie bonding us, but it seems like having a child together is also a real bond.”

But that legal and societal protection is not equally available to all couples in Italy: same-sex civil unions were famously legalized in 2016, making Italy one of the last Western countries to do so. The policy came with some prominent exceptions: civil unions, but not same-sex marriages, would be recognized. Adoption rights were also not granted to same-sex couples.

And there will likely always be politicians hearkening back to the family values of the Catholic church, the same family values that Mussolini’s Italy wanted to preserve. In 2018, Italian senator Simone Pillon, of the right-wing Lega party, brought forth a proposal for the “perfect co-parenting,” in which a child of separated parents would have to spend equal time between the father and mother and the parents would split the child’s education costs evenly. The proposed legislation was so controversial that the United Nations’ Special Rapporteur on violence against women even wrote a letter to the government, calling it a “potential serious retrogression in the advancement of the rights of women and their protection from domestic and gender-based violence in the city of Rome and throughout Italy.” The proposal also triggered organized protests in Italy.

In the more than 50 years since Italians were first granted the ability to divorce, the statistics reveal an interesting truth: perhaps what they really wanted was the freedom not to marry at all.